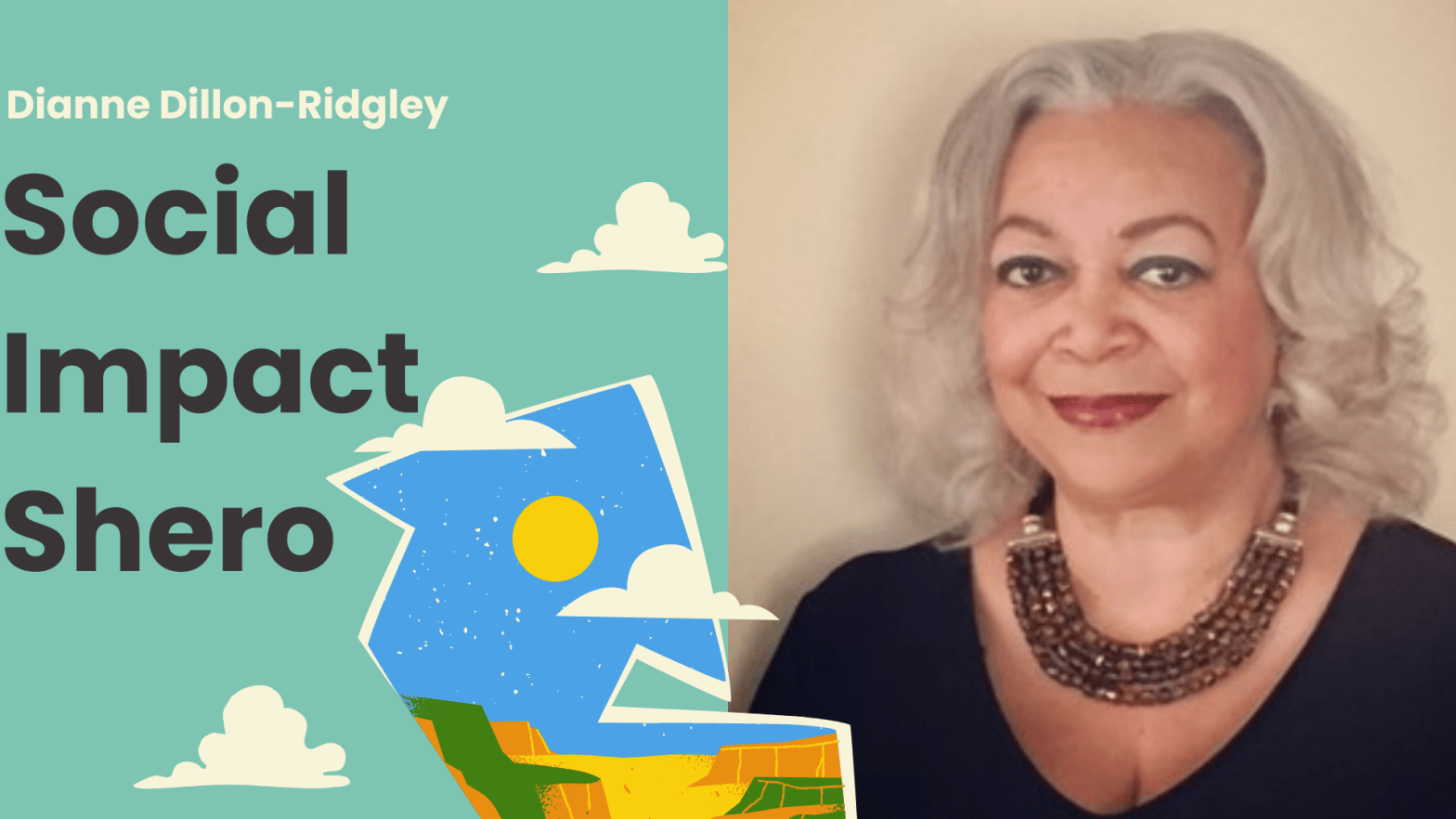

An interview with Dianne Dillon-Ridgley

We could have been sitting on the porch, sipping tea and chatting like Aunty to niece. But we were on a phone call, miles apart, and not technically family. This was only our second conversation. But I could feel the mother’s love in her heart as Dianne shared her childhood stories, inviting me (and all of you) into the thought process of a lifelong social justice warrior, fierce advocate for women’s rights, and pathbreaker in sustainability. Her story began like this:

The Power of Words

She sank down into her chair, feeling the eyes of all the other students burning into her. It seemed they were all asking, “Why didn’t your people just get up and walk off the plantation?”

Dianne was in 7th grade. The only Black child in her class in a progressive integrated Kansas City junior high school circa 1963. They had been going through the typical American history textbook that day, and just reviewed the requisite three paragraphs on slavery plus two or three Black heroes: Harriet Tubman, Du Bois, and someone else, maybe Carver?

My people were slaves.

This narrative, these words, starved Dianne of her identity, self-worth, and dignity. (It’s sobering to note that I had nearly the same experience in 1993. A full 30 years later.)

People may feel outside of words, but they don’t think outside of words. Words carry with them thoughts from one mind to another. And in 1963, society generally thought in terms of Black inferiority. Or more accurately, white supremacy.

Sister-in-law. Illegitimate. Hero. Slave.

If we make an intentional exchange of certain words for those that include and affirm, we might change our vocabulary. For example, looking at the list above, Dianne would prefer “sister-in-love” to convey a choice to embrace another person into the family. Let’s scratch out “illegitimate” entirely. It suggests an identity that is less than human, and doesn’t acknowledge the innocent child who happened to be born outside the construct of marriage. Shero is gender affirming. “Enslaved people” communicates that slavery is not who you are, but what colonizers did to your people group.

The fight for racial justice has always included a fight for the words and narratives that truly describe people rather than box them in.

Ms. Rains and the students in Dianne’s 7th grade class were not intentionally hostile. They simply were not equipped or properly informed. There was a missed opportunity for the teacher to expand on the text. To provide students with more context relating to pre-Civil War circumstances, for example, or how things changed with the fugitive slave laws.

The aftertaste of the narrative provided (or the lack thereof) in class left even more unspoken questions, like, “why can’t Black people just get over it now and pull themselves up by their bootstraps?”

They didn’t have bootstraps.

It’s funny how people in our generation wonder why they should give up what they have now for something like reparations. They think, “So what if my great grandparents were enslavers? We don’t own any slaves now.” So they owe nothing.

But we are just beginning the road to systematically demonstrate the institutional aspect of racism. We are just now considering ideas like “generational wealth,” where an inheritance, property, an education, and freedom from debt snowball from one generation to the next. We’re just scratching the surface on the idea of generational trauma. Consider that African Americans were:

Systematically disempowered:

The economic and legal construct of slavery in America was precisely designed to steal labor for one race’s direct financial benefit. To maintain this construct, for example, enslavers passed laws across the South severely punishing anyone (black or white) who would dare to teach enslaved people to read. Laws excluded enslaved people from owning property, getting [paying] jobs, and viewing themselves as equals to those of a lighter shade; the 3/5 compromise was codified in the Constitution. Enslavers distributed special Bibles to enslaved people with ideas about freedom and equality excluded. In many cases, enslaved Black people had never left the plantation grounds in their entire life. How could they be expected to just “walk off the plantation”? Where could they go? What could they do?

Systematically traumatized:

Enslavers intentionally split up nuclear families and emasculated Black men to deny families of their collective power. They brutally beat and murdered their “property” as routine discipline. They chopped off limbs of runaways, and raped Black women (did you know there were special underwear for enslaved women with holes in the crotch for easy access by their enslavers?). Multiracial children watched their fathers bequeath an inheritance to their white siblings. Lynch mobs gathered to torture, burn and hang their victims, leaving them on display as a marketing message for their cause.

Systematically vilified:

The movie “Birth of a Nation” (1915), aired in the White House by Woodrow Wilson, pioneered new creative approaches to cinematography. It also attempted to rewrite history. “Blacks… are portrayed as the root of all evil and unworthy of freedom and voting rights. …In contrast, the KKK is portrayed in a heroic light as a healing force restoring order to the chaos and lawlessness of Reconstruction” (source: Brittanica). Millions saw the movie; possibly the first box office hit, and it sparked the rebirth of the KKK. It’s wild to think that The White House promoted domestic terrorism.

Systematically excluded:

A few weeks ago (Labor Day), we celebrated Frances Perkins (as we should!), the first woman to serve in a cabinet position as Secretary of Labor under FDR. She is credited with many labor rights improvements, including social security (1935). Sadly, domestic laborers (majority of Black women) and agricultural workers (many Black men were sharecroppers) were specifically excluded from a share in the wealth. This represented 65% of the Black labor force, and those most in need (Heather McGee writes about this in her book, The Sum of Us.)

Systematically segregated:

The GI BILL (1944 – benefits for veterans) was great for education funding and FHA loans for housing. But in the descriptives, home loans had to be for single-family dwellings. Black veterans often lived in multi-family (e.g. duplex or triplex) dwellings and could not afford single-family homes, even with help. Moreover, the widespread practice of redlining legally excluded Black families from single-family neighborhoods. This cemented their poverty and locked them into crowded neighborhoods. Not to mention Jim Crow laws, sweeping job discrimination, and constant microaggressions.

Systematically disenfranchised:

Aside from the blatant voter suppression of the past (and present), there is a huge problem with incarceration. Currently, people in prisons (disproportionately Black males) are counted in the census to increase the population, which results in higher government payments to certain counties. Incarcerated people don’t receive any benefit, however. They cannot vote.

Brutal terrorism was the norm for hundreds of years, with horrific effectiveness. The goal was to systematically prevent escape, empowerment, or any form of success.

Psyche Restored

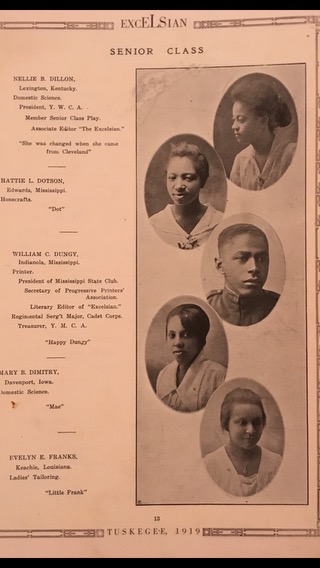

Dianne’s mom was a clinical psychologist. Both Dianne’s parents went to college. Her mother’s father had finished med school in 1917. Grandma had worked with Melvin B. Tolson (the inspiration for the movie The Great Debaters) when they were both professors at Langston University in Oklahoma.

When Dianne got home, she told her mother about the awkward moment she had in class. Mom pulled down original copies of The Souls of Black Folk, written by W.E.B. Du Bois (who received a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1895, and became a best-selling author and activist), and a signed copy of Tolson’s book, Rendezvous with America (which includes his award-winning poem, “Dark Symphony”). When Mom had read a few passages, she underscored that Black people are more than former “slaves.” They were always capable of brilliance in thought and word, as displayed in those published poems, essays, and best-selling books.

“We’ve been fine all along,” she soothed. “It is a construct of society to make you doubt yourself and never feel confident in who you are.”

Dianne was fortunate to have a family who could help her counter the narrative in that textbook. And in many ways, Dianne has spent her life helping the next generation counter false or incomplete narratives, too.

For a Better Future

Dianne majored in math and philosophy at Howard University. Early on after college, she interned at the Environmental Protection Agency. For several years, she was the UN representative for the World YWCA, advocating for education and political access for women across the globe.

By presidential appointment, Dianne participated in the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, 1997 UN General Assembly on the Rio results, and the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development. She’s the only person on the U.S. Government Delegation to attend all three groundbreaking events for global accountability and agreement around environmental protections.

For many years, she served as Director of the board at Interface, Inc., the world’s largest modular carpet tile manufacturer and a leader in sustainable design. She has served as CEO of Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) and the Women’s Network for Sustainable Futures.

Dianne is generous with her time, chairing or participating on the boards of several dozen organizations, some for more than a decade. This includes the National Wildlife Federation, Integrated Strategies Forum, Oxford University Commission on Sustainable Production and Construction, Auburn University School of Human Sciences Advisory Board, University of Iowa Tippie School of Business Advisory Board, and the Intentional Endowments Network. She has served on the Board of Trustees for the Center for International Environmental Law. She was the first Black person and woman to serve as Chair of the board for the River Network.

Never settling for the status quo, Dianne helped found 100 Grannies for a Livable Future, and Plains Justice, a Great Plains energy and environmental law center.

Awards

She has received multiple honorary doctorates, including from the Illinois Institute of Technology, and numerous other awards. Recently, Dianne received the E-News “Pave the Way” award for pioneering women in sustainability. In 2022, Howard University honored Dianne with their annual Post Graduate Achievement Award (note: the first honoree was the illustrious Zora Neale Hurston). Howard posted a video summarizing some of Dianne’s achievements:

The list could go on. Did we mention that she is one of our sheros?

Young Inspiration

Dianne finds inspiration spending time with the younger generations. Discovering the world anew through the eyes of a 3-year-old is both rejuvenating and hope-inspiring.

As a matter of fact, Dianne found her lifelong calling to fight for justice at a young age.

When she was a senior in high school, Dianne submitted an essay for a youth organization in which she was a member. Dianne didn’t think she had a chance to win – someone from her region had received that honor just the year before. She entered anyway.

She wrote about the four girls who had lost their lives on September 15, 1963 at 16th Street Baptist, a church that was bombed by white supremacists. It had been an important location for activists during the Civil Rights movement.

One of the girls, Carole Robertson, would have been around Dianne’s age. In part of the essay, Dianne wrote to Carole’s parents, committing to live her life the way Carole was denied the opportunity to do. The judges unanimously chose Dianne.

Dianne closed our interview with these words: “Indeed, I have tried to live up to that commitment. We owe that to all who have been martyred by racial terrorism.”

With Gratitude

Today, we honor Dianne for her lifetime of commitment. We have been inspired, and we hope hearing about one of our sheroes has given you fuel to do more good, too.

About Social for Good